Meet Dr. Christina Belanger

Learn more about the department of Geology and Geophysics newest paleontologist who joined last year, Dr. Christina Belanger

Sep 27, 2018

Dr. Christina Belanger was an undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) in the College of Creative Studies. This program is often described as the graduate school for undergraduates. Belanger had an emphasis in Biology, but also took core geology courses as a paleontology-driven student. Belanger did undergraduate research on Pleistocene molluscan fossils preserved in the Isla Vista Cliffs that extended along the coastline walking distance from campus. UCSB is also where Belanger started working with foraminifera – single-celled protists that make calcareous shells, which preserve well in marine sediments – to reconstruct paleoclimate.

After UCSB Belanger went directly to a Ph.D program at the University of Chicago in the Department of Geophysical Sciences where she designed a project looking at biotic responses to middle Miocene climate warming (~18 million years ago) preserved in sea cliffs along the Oregon Coast. Belanger went into the project thinking she’d see warm water species move into the site as temperatures climbed over the 2-million-year record, but it didn’t happen. Instead of temperature driving the changes in the communities of marine molluscs (clams and snails) and foraminifera, changes in marine productivity and an abrupt decrease in seafloor oxygenation affected the faunas. Only species tolerant of low-oxygen conditions remained by the end of the record. But tolerance did not mean they were thriving – some clam species found the environment so stressful that they grew slower and died at a much smaller size than when conditions were more favorable conditions.

Today, low-oxygen conditions are increasing along many coasts, include along Oregon, as climates warm. Windows into past ecosystem changes from the paleontological record like this one on the Oregon Coast can help us forecast, and prepare for, future ecosystem change. Belanger graduated with a Ph.D in 2011 and started a one-year post-doc at the University of Chicago working with a global database of marine bivalve occurrences built by Dr. David Jablonski and collaborators over decades. She merged their data with global oceanographic data such as temperature, productivity, salinity and found that oceanographic data alone could predict the distribution of bivalves across the globe. Changes in the species you found from one place to the next mapped almost perfectly with changes in environment – this means we can predict how species distributions will change if we know how environments will change. While a post-doc, she also began teaching as a lecturer at Lake Forest College where she developed a course called Global Environmental History and taught introductory geology to Environmental Science majors.

In 2012, Belanger moved to Rapid City, South Dakota to start her first tenure-track faculty position at South Dakota School of Mines and Technology (SDSMT) in the Department of Geology and Geological Engineering. As part of her position, she was also the Curator of Microfossils in the SDSMT Museum of Geology. While there, she helped obtain funding from NSF and ILMS to digitally catalog the collections and received her first introductions into curation and museums. Belanger also learned about new geological environments she hadn’t worked in before like the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway and started research on fossilized hydrocarbon-seep faunas that from conical structures locally called “tepee buttes” with one of her students. In the 5 years she spent at SDSMT, she taught graduate and undergraduate classes in Earth History, Paleontology and Oceanography, supervised 10 senior research projects, 8 M.S. students and 1 Ph.D student, Sharon, who transferred with me to TAMU.

In the Summer of 2013, Belanger was a shipboard micropalentologist for IODP Expedition 341 to the Gulf of Alaska where she served as a benthic foraminifera specialist. They spent 2 months a sea and found more foraminifera than expected to see – usually the waters of the North Pacific are so corrosive that carbonate does not preserve well. However, high sedimentation rates from glacial erosion protected the fossils and their variation through time can help reconstruct the history of sea floor oxygenation, temperature, productivity, and sediment transport in the Gulf of Alaska.

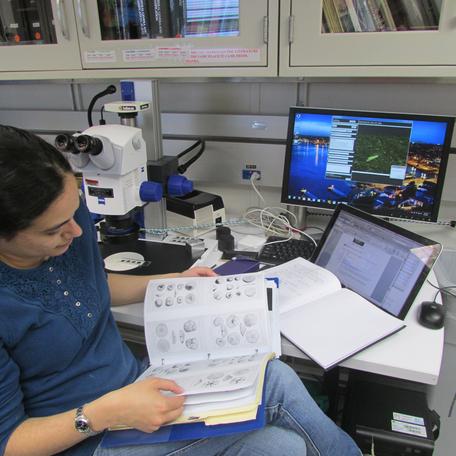

Belanger’s research focuses on understanding how organisms respond to environmental change and identify which environmental factors they primarily respond to. This information is integral to understanding how future climate change will affect modern biotas as well as to inform efforts to sustain biodiversity and economically important fisheries. Shelled organisms, such as molluscs and foraminifera, are abundant and well-preserved in the fossil record and in museum collections of modern specimens. These preserved assemblages allow longer-term perspectives on biotic response and climate change - millennia to millions of years - than is possible in exclusively present-day ecological studies. The fossil record also allows trends in these natural communities to be analyzed before, during, and after changes in climate without needing to wait for the events to occur in real time. Belanger is currently funded by the National Science Foundation PaleoPerspectives on Climate Change (P2C2) program to study low-oxygen events in the Gulf of Alaska over the last 60,000 years. This project uses materials she helped collected while aboard IODP Expedition 341 in Summer 2013 and is funding a current TAMU PhD student, Sharon.

Belanger is currently wrapping up the data collections stage of the P2C2 project with graduate student Sharon and undergraduate researchers, including Calie Payne and Pablo Cavazos, at TAMU and are entering the writing and synthesis phase of that project.

Taken by Susan Kidwell, Belanger's dissertation advisor in Spring 2006 in Oregon.

Sitting in Wolf Camp Hills looking for fusulinids and marine inverebrate in Permian limestones. Photo Credit: Eileah Simms. Taken July 2018.

In the micropaleontology lab aboard the Joides resolution trying to identify benthic foraminifera.

Taken by Susan Kidwell, Belanger's dissertation advisor in Spring 2006 in Oregon.